The Harvard Family Research Project separated from the Harvard Graduate School of Education to become the Global Family Research Project as of January 1, 2017. It is no longer affiliated with Harvard University.

Volume XI, Number 4, Winter 2005/2006

Issue Topic: Professional Development

Spotlight

Teacher Professional Development: How Do We Establish It and Know That It's Working?

As a public elementary school principal, first at the Mason School in Roxbury and now at the Murphy School in Dorchester, I saw that professional development workshops did little to change instructional practices in the classroom. What worked were collaborative, effective methods of professional development for improving instructional practice and, in turn, student achievement.

Principles and Practices of Professional Development

Teachers first at the Mason School and then at the Murphy School worked together to develop a set of effective professional development practices, which embody principles of teacher ownership, accountability, and instructional consistency. Here are some of the steps we took:

Visiting other schools. Teachers visited a high-performing school in the suburbs and were struck by the excellence of student work. This experience shaped our vision for professional development—a vision that embodies “reciprocal responsibility,” whereby the principal provides adequate professional development and the teachers identify necessary supports and implement practices. To fund this professional development, we had to redefine our resources as more than just money but also as time, materials, and job descriptions.

Designing a personal professional development plan. In all Massachusetts public schools, teachers create individual professional development plans approved by the principal. At the Murphy, we focus these plans on improving our teaching of reading, writing, and math. Plans still include attendance at outside workshops, but teachers are also responsible for applying learning in their classrooms and sharing information with their colleagues.

Induction of new staff. Each fall, incoming Murphy School teachers, paraprofessionals, and substitute teachers participate in modules designed by lead teachers to orient new staff to “the Murphy way” for teaching math and literacy, managing discipline, and including students with special needs. This practice extends beyond the district's mentor program to provide consistency at the school level and to give new teachers a team of people, rather than just one mentor, to whom they can go for help.

Collaborative coaching and learning. The idea of coaching arose from the teachers themselves, who requested a consultant to support their classroom instruction. Now, literacy and math coaches have become central to professional development, and teachers at the Murphy nominate their colleagues within the school to serve as coaches.

Every two weeks, all teachers from each grade convene with a math or literacy coach for 90-minute sessions to participate in a preparation session, an in-class demonstration, and a debriefing. This job-embedded approach allows teachers to see firsthand how students respond to new practices and gives teachers in each grade and across grades a consistent set of tools and the freedom to express individual variations.

Exercising teacher leadership. Murphy School teachers share their skills and knowledge with others by teaching district professional development courses, overseeing other adult learners in the school (e.g., resident teachers, graduate interns, and student teachers), serving as a site for visits by other schools, and writing for a teacher audience (see box).

|

|

|

|

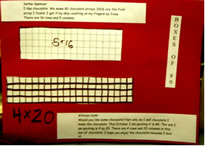

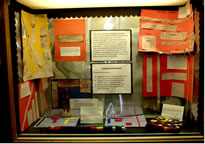

| Student work is prominently displayed throughout the Murphy School in classrooms, corridors, and foyers. The quality of student work produced is one way the school gauges the quality of instruction and professional development. (Photos: Lauren Grace, Murphy School) |

|

Measuring Professional Development Efforts

A simple count of hours revealed that the Murphy and Mason teachers spent three times as many hours per year in professional development activities as are required by the district. The practices we use to determine if these professional development efforts are working have become integral parts of the schools and have focused strongly on student learning:

Hard data. In 3 years at the Mason School, students moved from performing in the lowest 10th percentile on standardized reading and math tests to the top 10th percentile. This helped earn the Mason School a professional development award from the U.S. Department of Education.

Compelling evidence of effective professional development at the Murphy School comes from concrete data by the district's research and evaluation unit and the Massachusetts Department of Education, which correlates these activities with improved student performance. At the Murphy, 58% of students failed the state math exam in 1999. Now, the percentage has been reduced to 11%, and the Murphy was named a Compass School by the Massachusetts Department of Education.

Teachers receive training to understand and use student performance data to assess the performance of both individual students and entire grade levels. When a cluster of teachers noticed low scores on a test item for reading comprehension, they looked to the one teacher whose students performed higher on that task and adopted her practices as their own across the grade level.

Visual displays of student work. Convincing visual evidence of teacher learning and its subsequent impact on students is captured in the display of student work on walls throughout the school. Posting children's work makes teacher practice public and holds teachers accountable to colleagues, parents, and other community members.

Learning walks. Each day, as principal at the Murphy School, I conduct “learning walks” through classrooms to observe instructional practices and give feedback to teachers. Using a protocol of description, inference, and feedback, I offer teachers face-to-face or written input on their practice each week. Teachers are held accountable to me and to teacher colleagues in other ways as well—for example, by reviewing each other's student work in grade-level teams.

Related ResourceBrochu, A. M., Concannon, H., Grace, L. R., Keefe, E., Murphy, E., Petrie, A., & Tarentino, L. (n.d.). Creating professional learning communities: A step-by-step guide to improving student achievement through teacher collaboration. Dorchester, MA: Project for School Innovation. Available at www.psinnovation.org/PSI/btft12.html |

School- and district-level supports facilitate these professional development and assessment practices. District flexibility in how school funds are spent, permission to develop a school-based mentoring program in lieu of the district program, and a district commitment to professional development aided work at the Murphy School, as did whole school staffing and budgeting at the school level. At both schools, the deep commitment of the teaching staff has been at the heart of successful professional development design, implementation, and assessment.

Mary Russo

Principal

Richard J. Murphy School

1 Worrell Street, Boston, MA 02122

Email: murphy@boston.k12.ma.us