The Harvard Family Research Project separated from the Harvard Graduate School of Education to become the Global Family Research Project as of January 1, 2017. It is no longer affiliated with Harvard University.

Volume X, Number 3, Fall 2004

Issue Topic: Harnessing Technology for Evaluation

Questions & Answers

A Conversation With Jonny Morell

|

| Jonny Morrell |

Jonathan (Jonny) Morell is an organizational psychologist who researches and writes about how organizations change and about how their internal dynamics are influenced by political, social, economic, and technological environments. Much of his research and evaluation concerns the nexus of business processes and information technology. Dr. Morell is editor-in-chief of the international journal Evaluation and Program Planning and is on the editorial boards of the International Journal of Electronic Business and the International Journal of Services Technology Management. He is also a senior policy analyst at the Altarum Institute, a nonprofit institution whose mission is to promote sustainable societal well-being by employing new knowledge and decision support tools to solve complex systems problems in the healthcare, national security, and energy, environment, and transportation sectors. Dr. Morell holds a Ph.D. in psychology from Northwestern University.

What contributions can technology make to evaluation practice?

First, we need to define the term technology. Here, I am thinking of technologies based on electronics, networking, and information processing. These include personal data assistants, cell phones with cameras, computers, global positioning systems, and many others. The common threads are information capture, processing, and transmission, all fueled in large measure by electronics. Technology, in this sense, is therefore a collection of tools, each useful for a different purpose, each to be drawn on as needed.

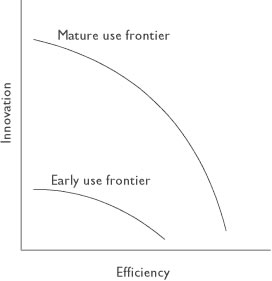

I see the value of technology on a two-dimensional grid (see the figure below). The x-axis represents efficiency—doing the same thing you always did, but better, faster, and cheaper. The y-axis represents innovation—applying technology to address questions you did not realize could be addressed or that you did not realize even existed.

|

| Relationship Between Efficiency and Innovation in Technology Application |

Most people begin somewhere on the middle of the efficiency axis and very low on the innovation axis. They see that technology can make them more efficient but not that it can help them innovate. As they move along the efficiency axis and become more experienced with technology, however, they see new possibilities and tend to move farther along on the innovation axis as well.

Evaluators need to appreciate what technology will allow them to do. The greater the appreciation, the more they can innovate. Take online surveys, for example. At first blush, they seem useful because they are efficient. They allow automated data entry, fewer mailings, lower cost in reaching respondents, greater ease in tracking them, and so on. Those are the reasons that first drew me to the technology. Soon after, I came to see that the technology would also allow me to ask a new class of questions.

By way of example, I'm involved in a study of how various organizations use six continuous improvement methodologies. In the course of this study, I realized that online surveys made it possible to build a novel (to me, at least) kind of “if-then” question. In this design, if a respondent says “yes” to using any three of the six continuous improvement methods, the survey then returns a specific set of questions. If the respondent indicates using two methods or fewer, the survey returns yet a different set of questions. Without computer-assisted technology I never would have considered this line of questioning.

While that example involved data collection and processing, the possibilities also extend to evaluation design and interpretation. Technologies like the Internet, the World Wide Web, collaboration technologies, and conference phoning extend possibilities for collaboration and participation among stakeholders, evaluators, and anyone else who has something useful to contribute. The efficiency such technology offers is obvious. As the cost of telecommunications decreases, accessibility increases. More people can be involved without having to travel and without having to be involved all at the same time. And consider what can happen as such technology leads to greater opportunities to get stakeholders involved in interpreting data or agreeing on critical evaluation questions. The possibilities go beyond “faster and cheaper”; they make our work participatory in ways that would be difficult or impossible without technology.

Modeling and simulation technology offers yet another example. This is a specialty, requiring special software and a lot of expertise. While I am not an expert, I can see many possible applications to evaluation. For instance, observing a model or simulation can provide insight into how a system is working, even if the model does not reflect the “true” internal operations of the system. Also, it is the only way I know to see the effects of feedback loops and interactions between parts in the system, as these involve nonlinearities that do not show up in the normal logic models¹ we construct.

That said, models that are practical for us to build may not work well enough to provide useful guidance. And, models that would be useful might require a greater degree of program specification than we can muster. Even with these reservations, I know evaluators are experimenting with using this technology. I am motivated to do this, too, because I am convinced that our logic models are much too simple to explain the realities we deal with, and I am intensely curious as to whether modeling and simulation technologies can help.

Most of these examples have a quantitative focus, but more qualitative topics are relevant as well. One example is the virtual focus group, in which individuals can participate simultaneously from different locations or via asynchronous online bulletin boards that are active for several days and accessible at times most convenient for participants.

What methodological issues or cautions apply when using technology for evaluation?

There is no single answer. It depends on the technology being used. For example, using the Internet to conduct virtual focus groups requires a different set of skills than doing computer-assisted telephone interviewing. But several pieces of general advice are important. First, understand that without deep knowledge of a specific technology, one can get into trouble. I speak from experience. I used an online survey package for a project that required quite a lot of if-then question branching. Because many people had input into many drafts of the survey, questions were revised numerous times. As we made revisions, I discovered that the branching logic² of the survey package was tied to the precise wording of the questions. For instance, changing important to critical in a question's wording required re-specifying the branching logic. I never even thought about checking this when selecting the survey package.

We assume technology can do various things that make sense to us. Sometimes we are right; sometimes we are not. As a general rule, assume the worst. My definition of an expert is someone for whom a given problem is routine. Get expert advice (or become an expert yourself) on the precise technologies you plan to use.

The second piece of advice is to remember the basics. No matter what the technology, the basics will always be important. Reach appropriate stakeholders. Get representative samples. Use reliable measures. Attend to the logic of causal inference. Understand program logic. All of this is, and always will be, the foundation of good evaluation.

Finally, beware of technology's seductiveness: It can be wasteful. When all is said and done, technology is just a tool. Like all tools, it is value neutral. Technology can make for much better evaluation, but when inappropriately or ineffectively applied, it can also make evaluation worse. We may have to use technology because our clients expect us to, or because fads make it hard to publish if we don't. But we should be realistic about when we need technology and for what purpose.

How should evaluators think about the opportunities that technology offers?

When people think of technology they tend to think of data manipulation and analysis. A broader way to look at the use of technology is to assume that it may be useful at any point in the evaluation life cycle, from planning through design, implementation, analysis, and reporting. The challenge lies in appreciating the possibilities along that cycle.

At the planning stage, technology affects methodology choices. For instance, easy access to secondary data may influence choices about the need for primary data collection. With respect to implementation, consider any multisite evaluation where different people are doing evaluation in different locations but in a common way. Technology can be used to manage the various evaluation teams or to exchange useful experiences from each location.

As for reporting, consider the example of performance monitoring. Before, data could be collected and reported only at relatively long intervals (e.g., monthly, quarterly, yearly). Data were often useless if the reporting interval exceeded the time frame for corrective action. Now, technology offers the opportunity to tailor reporting to specific information needs. And, of course, the simple ability to post a report to the Web can have enormous consequences in terms of revealing findings to the public.

For more details on Dr. Morell's work see his digital scrapbook, at www.jamorell.com.

¹ A logic model illustrates how an initiative's activities connect to the outcomes it is trying to achieve.

² Branching logic refers to the decision rules built into a questionnaire that determine how a respondent moves from one question to the next.

Julia Coffman, Consultant, HFRP