The Harvard Family Research Project separated from the Harvard Graduate School of Education to become the Global Family Research Project as of January 1, 2017. It is no longer affiliated with Harvard University.

|

March 8, 2016 Why Thinking of Family Engagement as Continuous Across Time MattersMargaret Caspe

|

Related Resources

FINE Newsletter, Volume VIII, Issue 1

Professional Development Tools to Make Continuous Family Engagement Come Alive!

Commentary

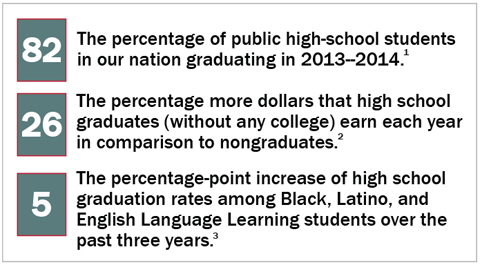

As we welcome the news that the nation’s high-school graduation rate is higher than ever before, we must continue to strive to improve graduation rates and to strengthen the role of families in helping students reach this important milestone. This role begins well before high school―in a child’s earliest years, and continues through adolescence. Take a look at, for example, a longitudinal study that followed children from low-income homes starting at birth through age 23. Children who experienced good parent–child relationships in early adolescence and whose parents were engaged in their education in the middle childhood years had high graduation likelihoods. Comparatively, children who had poor relationships with their parents were more likely to drop out of high school, despite doing well academically and socially.4

Family engagement also plays a big role in where high school graduates go to college and whether or not they graduate from postsecondary institutions. When schools and communities help families understand the college application process, make sure they have access to college savings programs, and assist families in helping students find a good college match, students are more likely to stay in college and earn a degree.5

Consider, though, that 47% of white adults held at least a two-year college degree in 2015, in comparison to only 33% of African American adults and 23% of Latino adults.6 In this context, family engagement―continuous across time from cradle to career―is a matter of equity. Through school and community partnerships and peer support, families make sure children start kindergarten strong, stay on a pathway to college, graduate from high school, and complete college. Having a postsecondary degree is crucial―it is beneficial for both positive life outcomes for individuals and for our society as a whole.7

While family engagement often starts out strong in the early years, it tends to decline over time, even as early as kindergarten, so that by the time students are in high school, family engagement has often fallen off precipitously.8 Persistent encouragement from teachers and other educators acts as a lever to reverse this trend and promote continuous family engagement.9 Additionally, welcoming schools, teacher invitations for families to participate, and educator guidance for families to support learning can reaffirm families’ important roles and strengthen their feelings of efficacy, both of which are known to motivate family engagement.10

Thus, preparing educators to develop positive relationships with families is essential, especially when teachers are unfamiliar or uncomfortable with families from different cultural backgrounds and socioeconomic circumstances.

In this issue of the FINE Newsletter, we offer educators a set of tools to facilitate family engagement across time. Over the next three weeks we will introduce interactive cases that demonstrate how family engagement matters at three critical junctures in a child’s life: the transition to college, the transition to middle school, and the transition to kindergarten. By providing cases that are based on real-world stories, our hope is to make the idea that family engagement is continuous across time come alive. Together, or on their own, these cases will help you:

- Understand perspectives of families that are often disenfranchised by the educational system during transition points.

- Recognize key developmental and family engagement issues at different times in a child’s life.

- Appreciate how thinking about family engagement as a shared responsibility and as a process that spans all the settings in which children and youth learn can help promote sustained engagement over time.

- Reflect on data and larger organizational and societal issues and trends that influence each person’s behavior.

Try out these interactive cases and to tell us what you think at fine@gse.harvard.edu. And if you aren’t already a FINE Newsletter subscriber, join now so you don’t miss a thing!

This resource is part of the March 2016 FINE Newsletter. The FINE Newsletter shares the newest and best family engagement research and resources from Harvard Family Research Project and other field leaders. To access the archives of past issues, please visit www.hfrp.org/FINENewsletter.

1 National Center for Education Statistics. (2015, December). Common core of data. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/tables/ACGR_RE_and_characteristics_2013-14.asp

2 National Center for Education Statistics. Fast facts. (2015). Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=77

3 National Center for Education Statistics. (2015, December). Common core of data. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/tables/ACGR_RE_and_characteristics_2013-14.asp

4 Englund, M. M., Egeland, B., & Collins, W. A. (2008). Exceptions to high school dropout predictions in a low-income sample: Do adults make a difference? Journal of Social Issues, 64(1), 77‒94.

5 Smith, J., Pender, M., Howell, J., & Hurwitz, M. (2012). A review of the causes and consequences of students’ postsecondary choices. Retrieved from http://research.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/publications/2014/9/literature-causes-consequences-students-postsecondary-choices.pdf

6 Young Invincibles Student Impact Project. (2016). 2016 state report cards. Retrieved from http://younginvincibles.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/YI-State-Report-Cards-2016.pdf

7 College Board. (2013). Education pays 2013: The benefits of higher education for individuals and society. Retrieved fromhttp://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/education-pays-2013-full-report-022714.pdf

8 Hill, N. E., & Chao, R. K. (Eds.) (2009). Families, schools and the adolescent: Connecting research, policy, and practice. New York: Teachers College Press; Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., & Pianta, R. C. (2000). An ecological perspective on the transition to kindergarten: A theoretical framework to guide empirical research. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 21(5), 491‒511.

9 Hayakawa, M., Englund, M. M., Warner-Richter, M., & Reynolds, A. J. (2013). Early parent involvement and school achievement: A longitudinal path analysis. NHSA Dialog: The Research-to-Practice Journal for the Early Childhood Field, 16(1), 200‒204.

10 Hoover-Dempsey et. al. (2005). Why do parents become involved? Research findings and implications. Elementary School Journal, 106(2) 105-130.