The Harvard Family Research Project separated from the Harvard Graduate School of Education to become the Global Family Research Project as of January 1, 2017. It is no longer affiliated with Harvard University.

|

October 2010 Making Data Come Alive for Families through Young Children’s PlayAmy Horenbeck

|

FINE: The Family Involvement Network of Educators

![]() The FINE Newsletter shares the newest and best family involvement research and resources from HFRP and other field leaders.

The FINE Newsletter shares the newest and best family involvement research and resources from HFRP and other field leaders.

FINE Newsletter, Volume II, Issue 3

Issue Topic: Using Student Data to Engage Families

Voices From the Field

Amy Horenbeck, training director from the Tools of the Mind program based at the Center for Improving Early Learning at the Metropolitan State College of Denver in Colorado, discusses a different approach to early childhood education and using children's work as a unique type of student data to track development and share children's progress with parents.

Quality early childhood assessment highlights young children’s strengths, progress, and needs; and best practice calls for assessment methods that are tied to children’s daily activities. However, collecting and using data in dynamic and interactive ways to inform instruction, to identify growth for individual children, and to engage families is difficult. Too often, early childhood data come in the form of abstract numbers or through a few work samples or anecdotal written explanations—that can feel subjective to families.

Tools of the Mind1 has found one way to overcome these challenges and to engage parents in their child’s development through data. Tools of the Mind (Tools) is an early childhood curriculum for preschool and kindergarten children, based on the ideas of Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky. The curriculum is designed to foster children’s executive function, which involves helping children regulate their social, emotional, and cognitive behaviors. The activities in the curriculum are designed to emphasize both executive functioning and academic skills, and the main medium through which this happens is mature make-believe play.

Steps in implementing children’s play plans:

- Children create a play plan. Every day before children play, they create a written plan for where they will play and what they will do. For example, a child might choose to play in the block area and build a tower or pretend to be a doctor (considered “dramatic play”).

- The plan is always “scaffolded” by the teacher. Scaffolding refers to a teacher’s role in supporting a child’s learning by providing the structures to advance to the next level. Every day, teachers note what children can do independently and then make a decision about the next skill that should be supported. For example, some children may need assistance forming a complete sentence to explain their ideas while others may need help creating a play scenario that involves their peers. Children represent their choice on their play plan using either scribbles, a drawing, or actual writing.

- Teachers “rate” the play plan. At the same moment that children create their play plans, teachers simultaneously “rate” the play plan according to a rubric designed by Tools that supports them in making instructional decisions that are based on understanding of child development. The rating rubric is modified for ages 18 months through 6 years of age and ranges from “PL," which represents the planning stage in which a child is just learning to make a choice, to “AP” in which a child knows the Alphabetic Principle and can make a word and sound it out (see text box below).

Sharing Data with Families: The importance of a shared understanding of child development.

|

| A young girl reads at Tools of the Mind. |

At the beginning of the school year, teachers reach out to families and hold orientations in which they explain the purpose of play plans and how to understand them. Teachers also send home newsletters introducing parents to the play plan rubric and how to interpret children’s work. These newsletters explain what is typical at different stages of development. This helps parents to interpret their children’s work in the same manner the teacher might. For example, parents would be encouraged to interpret a word such as “prncss” (princess) written by a child, not as an error but rather as a positive step towards becoming a reader.

Play plans are created daily, and each Friday, teachers send home four play plans and keep one play plan from that week for each child’s individual portfolio. Therefore, at the end of every week parents and children have four play plans that form the basis for a shared conversation about what was learned at school that week. In addition, at the end of each month the teacher analyzes the play plans from each week that were maintained in the child’s portfolio and notes each child’s growth in planning, play, and literacy, in addition to setting goals for that child for the next month.

Taken together, data in the form of play plans help support the parent–child relationship and the parent–teacher relationship.

Data supporting the parent–child relationship: Because children create their own play plans, they understand them and can explain them to parents when they come home each week. Thus, the child becomes a critical agent through which parents understand child data. Each play plan has built in memory “cues” that support children so that they can talk with their parents about what they did at school each day.

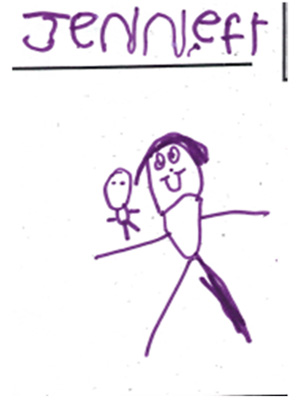

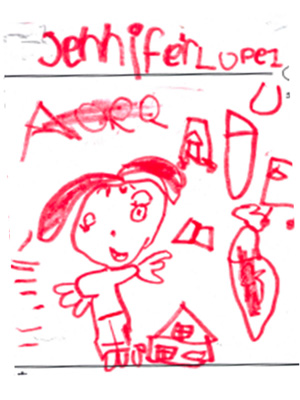

An example of two play plans showing growth over the preschool year.

Both play plans were developed by a girl named Jennifer who did not speak English as her first language. In September (left drawing), Jennifer was able to draw herself and a doll and indicate by pointing that she wanted to go to the dramatic play center. She required teacher assistance to follow through on her plan. By April (right drawing), Jennifer’s drawings and planning abilities are more mature. When asked about this Play Plan she told the teacher, "I am going to paint the house." When one looks at her plan one can clearly see a house, paintbrush, and easel. She was also able to independently carry out her plan without adult assistance. |

For example, activity centers are areas within an early childhood classroom where children can play, explore materials, and develop skills and knowledge. In Tools of the Mind, the activity centers are color-coded (e.g., green represents the dramatic play center, red represents the art center, or purple represents the block center). When children draw their play plan, they draw in the color of the center they are going to. Thus, even the youngest child who only draws in scribbles can describe his activities because he associates the color with the activity.

Moreover, teachers write on play plans in pen so that it is clear to parents what their children can do alone and what they can do with adult help; parents can also see what kind of assistance the teacher provides. By tracking their child’s growth each week through the child’s own words, writing, and pictures, parents are instantaneously involved in children’s data from the very start of the program.

Data supporting the parent–teacher relationship: Play plans are often used as the foundation for parent–teacher discussions. For example, when comparing two play plans, a teacher might point out the increase in the child’s ability to represent her ideas with symbols and the growth in her expressive language skills (see text box). But the play plan also allows the teacher to engage the parent in a discussion of the student’s ability to sustain attention, work with peers, and carry out plans independently.

Play plans allow parents to see children’s progression in very concrete ways. Parents can also visualize their child’s next developmental stage. Moreover, play plans are helpful if teachers must talk with parents about evaluation and referral services because they provide a data trail that touches not only on a child’s literacy development but also on other important abilities such as planning and being able to sustain attention.

In the future, Tools of the Mind seeks to expand teacher development to include modules that help prepare teachers to talk with families about data. Moreover, the Tools program is looking to expand its dynamic assessment approach into the mathematics domain in the kindergarten years. Upcoming evaluations plan to explore more concretely how parent engagement through play plans influences children’s growth and development.

This resource is part of the October 2010 FINE Newsletter. The FINE Newsletter shares the newest and best family involvement research and resources from Harvard Family Research Project and other field leaders. To access the FINE Newsletter Archive, visit www.hfrp.org/FINENewsletter.