The Harvard Family Research Project separated from the Harvard Graduate School of Education to become the Global Family Research Project as of January 1, 2017. It is no longer affiliated with Harvard University.

|

April 2016 Design Thinking: Catalyzing Family Engagement to Support Student LearningAllison Rowland

|

Article Information

- Full Text (HTML)

How can human-centered design strengthen family engagement? As a doctoral resident in Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Doctor of Education Leadership program, I am exploring this question in my work with the San Diego Unified School District. The district, the second largest in California, invited me to guide its efforts in developing a systemic approach to family engagement.

In collaboration with the district’s Parent Outreach and Engagement department and Crawford Community Connection, a local nonprofit, we organized and piloted a Design Thinking: Partnering with Families for Student Learning workshop. We wanted to call attention to the power of family engagement and facilitate a process whereby educators and community partners listen carefully to families and then take action with them to solve problems together.

Design Thinking: Partnering with Families for Student Learning Workshop, San Diego Unified School District

Who: 120 people, including families representing six languages, middle and high school students, teachers, principals, district staff, and community partners

Where: City Heights neighborhood in San Diego

When: Saturday, September 26, 2015, 9 a.m.–3 p.m.

Why: To generate ideas about how family-school-community partnerships can effectively support student learning and create investment for taking action on solutions—together.

Five Steps

Below is the process we used for our modified design thinking challenge.

1) Make the case and build relationships.

Ground the workshop in supporting student success. Right away, build connections across roles and use the research to demonstrate the essential role that families play in student learning. Schools often think about family engagement as limited to volunteering and being involved in school governance. While some families can take leadership roles and many families participate in school activities, all families can support their student’s learning in the home and in the community.

2) Create a design challenge.

A design challenge points to a goal that keeps participants focused throughout the workshop. Families and educators form small teams to address this specific design challenge: “How might we design a better way for families, educators, and community partners to support student learning—together?”

3) Build empathy.

Empathy is an understanding of people and what is important to them. Family members share what they feel, hear, and see about the school and their student’s education. Educators listen attentively without talking or interrupting. In this modified version of Design Thinking, the typical one-on-one interviews take place with the families in groups of 8–15 people.

4) Develop a prototype.

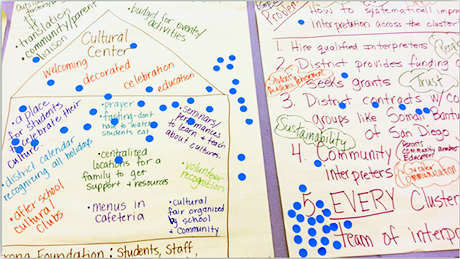

A prototype is a representation of the ideas—often, solutions to a problem—that emerges from the design challenge. In teams of 6–10 people, including educators, families, community partners, and students, each team reframes the design challenge based on what they hear from families and then “ideates” or brainstorms solutions. They use materials such as poster paper, sticky notes, and markers to create a visible representation of their ideas.

5) Choose a prototype.

Each team presents the problem they are trying to solve; a prototype as a solution; and the pros and cons of the prototype. Families and educators vote for the prototype they commit to testing and implementing together in future gatherings.

|

Sample prototype posters presented by design teams |

|

The blue stickers represent "votes" for the prototypes and next steps. |

Reflections

Challenges can be turned into opportunity.

Typically, in Design Thinking, listening and building empathy involve conducting one-on-one user interviews. Because of limited translation services, we decided to flip the way translation usually happens: The families conversed in their own languages, and the educators listened to the translated conversation in English on headsets. We listened to families speaking Karen, Kizigua, Somali, Spanish, and Vietnamese. The experience was profound— many educators had not heard families’ perspectives in such a direct way—families were empowered to speak to each other in their own languages. Educators and families reported the process built trust and often shifted their beliefs about each other.

Listening to families is a profound learning experience.

We found that the educators benefited tremendously from listening to the families speak during the empathy work. The educators’ role was solely to listen, and we instructed them not to interrupt or ask questions. It was an opportunity for the families to speak and share their stories. Following the event, the educators shared how deeply moved they were by the experience. Many of the educators noted that design thinking principles helped them to better understand their students and families.

The process works in many contexts.

Since the event, we have used design thinking techniques in multiple contexts yielding very similar results. We have been able to modify the experience to two to four hours rather than a full-day session, and we are currently building capacity for the process to become a cornerstone for a broader systemic approach in which each and every family is empowered to support their student’s learning.

Family engagement is about an “us with them” mindset.

The event instilled in participants a sense that families and educators are collectively responsible for this work. Tim Brown, CEO and president of the IDEO design firm, emphasizes that Design Thinking is based on an “us with them” mentality rather than an “us versus them” or an “us on behalf of them” mentality.1 An area superintendent shared with us that she has seen a shift toward an “us with them” approach following the event, noting that families and educators are working together when a problem arises and asking how they can solve it together. It is no longer that one party is approaching the other with a problem and asking them to solve it.

Design Thinking builds a fertile ground for partnerships.

The event had a strong and lasting impact, and we found that many of the educators who participated agreed that this modified design thinking process had led to action to improve family engagement at their school sites. The event was effective in building trust and stronger relationships between the families and educators, which we see as a critical first step in empowering families and increasing opportunities to develop effective partnerships.

Latest Developments

Since the pilot workshop, we have completed our first training of 15 school teams to lead Design Thinking: Partnering with Families for Student Learning workshops at their school sites.

A special thanks to Christina Simpson who contributed to this article. Christina is currently a student at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education in the Education Policy and Management program.